As I write this article, I have just finished an exhaustive read. It was one of those volumes that, unlike others that the eyes seem to devour effortlessly, proved persistently difficult to finish. Though I had set myself the task of reading it for the express purpose of writing about it afterwards, I found myself stopping and starting, taking a break from it’s highfalutin prose and verbose descriptions of scenes and settings to read other works that were more terse and taxed my imagination less. Yet, for all that, it was worth it, as for the arduous literary trek that it was, the way was also marked with gems as unique as the worlds in which they inhabit. The book in question I am pontificating about is Necronomicon: The Best Weird Tales of H. P. Lovecraft; a choice anthology of the writer’s works.

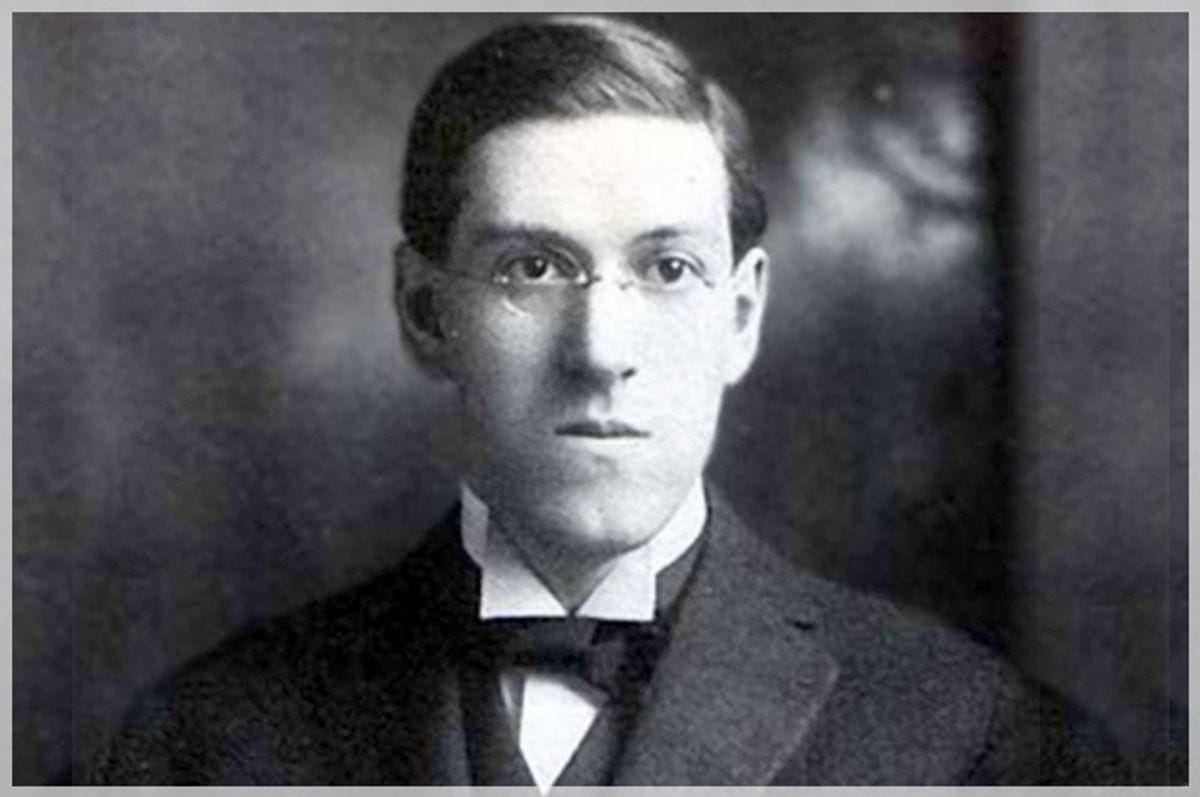

Howard Phillips Lovecraft was born on the 20 August 1890, in his grandparents’ home in Providence, Rhode Island. His childhood was not the easiest, marred by tragedy and ill health. His father, Winfield Scott Lovecraft, died when Howard was only eight-years-old of tertiary neurosyphilis, having spent time in an asylum after a mental breakdown five years earlier.

The young H. P. Lovecraft was raised predominantly by his mother and her extended family. Though he was surrounded by matriarchal care, his mother was, by most accounts, strongly puritanical in a distinctly New England, nineteenth century way. Lovecraft later confided in his wife, Sonia Greene, that it was the emotionally restrained, tactile-less and sometimes harsh manner of his mother that had a deeply harmful effect on him as a young boy. Due to bouts of sickness, in large part psychosomatic from prolonged nightmares and poor sleep, he did not attend school for very long, so was educated largely at home.

This was most fortunate for the young Lovecraft, as he was able to take full advantage of his family’s inherited wealth; the Lovecraft (or Lovecroft) name can be traced back to fifteenth century English aristocracy. In the attic of his family home in Providence, New England, was a tremendous collection of books, compiled over many years by his maternal grandfather, Whipple Van Buren Phillips. His mind blazing with the ghost stories his grandfather would sometimes tell him, and encouraged to read as an autodidact by all his family, the boy-Lovecraft would sometimes sneak up into the attic at night with a candle to immerse himself in one fable after another.

But another tragedy was to ail Lovecraft’s childhood once more, when at the age of twelve, his grandfather, after a string of bad investments, passed away, forcing his mother to sell his childhood home and the attic full of his beloved books. Shortly afterwards, the dreamworld of the precocious autodidact was brought to an abrupt halt; Lovecraft being sent to study at a local school he didn’t much care for. Though he had many interests that would later come through in his writing potently, because of his inadequate ability in mathematics, he was unable to pursue a career as an astronomer. In 1908 he left formal education once and for all, not to reemerge into public life for another nine years. It is now believed that for those lonely years, Lovecraft was suffering from severe depression.

The impression that reaffirmed itself to me repeatedly as I worked my way through Lovecraft’s stories was of a pre-modern sensibility confronting a modern world it had been dragged into, kicking and screaming; or, as Lovecraft might have put it: borne into by a monster after having succumbed to unconscious terror. A quote attributed to him in the documentary H. P. Lovecraft – Fear Of The Unknown1 suggests as much: “I’ve always had the subconscious feeling that everything since the 18th century is unreal or illusory, a sort of grotesque nightmare or caricature”.

In Lovecraft’s The Dreams in the Witch-House, the tension in attempting to reconcile the modern with the archaic opens the story brilliantly in just a few lines. “Possibly Gilman ought not to have studied so hard. Non-Euclidean calculus and quantum physics are enough to stretch any brain; and when one mixes them with folklore, and tries to trace a strange background of multi-dimensional reality behind the ghoulish hints of the Gothic tales and the wild whispers of the chimney-corner, one can hardly expect to be wholly free from mental tension”.

Though Lovecraft was very conservative in his outlook of the world and in his literary tastes, he managed to blend these seamlessly with a cosmology that is distinctly modern, i.e. that of infinite space and the prospect of an inter dimensional multiverse posited by quantum physics. The Shadow Out Of Time, in Lovecraft’s particular slow, creeping style, weaves these different elements wonderfully. The story (written in the first person as Lovecraft often did, setting an uneasy, subjective mood) centres around the academic Nathaniel Wingate Peaslee. After a catatonic episode, hinted at being demonic possession, Nathaniel describes part of his recovery so: “When I diffidently hinted to others about my impressions, I was met with varied responses. Some persons looked uncomfortably at me, but men in the mathematics department spoke of new developments in those theories of relativity – then discussed only in learned circles – which were later to become so famous. Dr Albert Einstein, they said, was rapidly reducing time to the status of a mere dimension”.

In his vivid dreams and delusions, Peaslee describes his visions thusly: “My conception of time – my ability to distinguish between consecutiveness and simultaneousness – seemed subtly disordered; so that I formed chimerical notions about living in one age and casting one’s mind all over eternity for knowledge of past and future ages”.

Later, when, inspired by his visions, Peaslee leads an archeological expedition into a desert wilderness marked with strange monoliths and relics, he falls into a kind of astral projection that takes him to an era of unrecorded history, among creations never before seen living or in the fossil record. “Secrets of the primal planet and its immemorial aeons flashed through my brain without the aid of sight and sound, and there were known to me things which not even the wildest of former dreams had ever suggested. And all the while cold fingers of damp vapour clutched and picked at me, and that eldritch, damnable whistling shrieked fiendishly above all the alterations of babel and silence in the whirlpools of darkness around.

Afterwards there were visions of the cyclopean city of my dreams – not in ruins, but just as I had dreamed of it. I was in my conical, non-human body again, and mingled with crowds of the Great Race and captive minds who carried books up and down the lofty corridors and vast inclines”.

Such an extract gives us a great example of Lovecraft’s weirdly articulate prose, in particular, his common use of the word ‘eldritch’, defined by the Online Oxford Learner’s Dictionary as “strange and frightening”. Along with this, it evokes such a scope of space and time as to make the reader feel quite diminutive when attempting to wrap one’s imagination around the vast distances and oddities Lovecraft describes.

But Lovecraft didn’t have to take us on a dream-quest through the void of the cosmos to find the incredible and horrific. In The Horror at Red Hook, Lovecraft plunges us into the uninviting streets of early twentieth century New York, ending in subterranean terror. A police detective named Thomas F. Malone is investigating a wealthy local man named Robert Suydam, and his possible connection to organised crime.

The investigation immediately takes a macabre and superstitious direction; Lovecraft’s depiction of early twentieth century New York being closer to an ancient Greek rendition of Hades, or a level from Dante’s Inferno, than a feeling of progressive urbanity. Drawn from his own experience of living in the roiling city, where life is driven entirely by commerce, Lovecraft writes in the first act of the story: “…as he reviewed the things he had seen and felt and apprehended, Malone was content to keep unshared the secret of what could reduce a dauntless fighter to a quivering neurotic; what could make old brick slums and seas of dark, subtle faces a thing of nightmare and eldritch portent. It would not be the first time his sensations had been forced to bide uninterpreted – for was not his very act of plunging into the polyglot abyss of New York’s underworld a freak beyond sensible explanation? What could he tell the prosaic of the antique witcheries and grotesque marvels discernible to sensitive eyes amidst the poison cauldron where all the varied dregs of unwholesome ages mix their venom and perpetuate their obscene terrors? He had seen the hellish green flame of secret wonder in this blatant, evasive welter of outward greed and inward blasphemy…”

Immediately afterwards, with a mastery of terse prose, Lovecraft very succinctly introduces Malone’s inner world and thoughts, evoking a thoughtful and worldly man that begrudgingly made a living fighting crime in the nightmare world of sober reality. “To Malone the sense of latent mystery in existence was always present. In youth he had felt the hidden beauty and ecstasy of things, and had been a poet; but poverty and sorrow and exile had turned his gaze in darker directions, and he had thrilled at the imputations of evil in the world around. Daily life had for him come to be a phantasmagoria of macabre shadow-studies; now glittering and leering with concealed rottenness as in Beardsley’s best manner, now hinting terrors behind the commonest shapes and objects as in the subtler and less obvious work of Gustave Doré. He would often regard it as merciful that most persons of higher intelligence jeer at the inmost mysteries; for, he argued, if superior minds were ever placed in fullest contact with the secrets preserved by ancient and lowly cults, the resultant abnormalities would soon not only wreck the world, but threaten the very integrity of the universe. All this reflection was no doubt morbid, but keen logic and a deep sense of humour ably offset it. Malone was satisfied to let his notions remain as half-spied and forbidden visions to be lightly played with; and hysteria came only when duty flung him into a hell of revelation too sudden and insidious to escape”.

The story takes one dark turn after another; Malone’s investigations embroiling him in a search for some missing children. When involved in a raid where an occult ritual was interrupted, Malone searches the basement and, like Peaslee at the site of his archeological dig, is forced unconscious as he swirls into some bottomless pit.

Though what happened next was explained away by ‘specialists’, Malone’s lurid memory of the events which followed haunted him, as they may haunt the reader; Lovecraft, in his typical storytelling style, not offering an adequate explanation as to why and how the events had transpired. “Avenues of limitless night seemed to radiate in every direction, till one might fancy that here lay the root of contagion destined to sicken and swallow cities, and engulfed nations in the foetor of hybrid pestilence. Here cosmic sin had entered, and festered by unhallowed rites had commenced the grinning march of death that was to rot us all to fungous abnormalities too hideous for the grave’s holding. Satan here held his Babylonian court, and in the blood of stainless childhood the leprous limbs of phosphorescent Lilith were laved…All at once, from an arcade avenue leading endlessly away, there came the daemonic rattle and wheeze of a blasphemous organ, choking and rumbling out the mockeries of hell in a cracked, sardonic bass. In an instant every moving entity was electrified; and forming at once into a ceremonial procession, the nightmare horde slithered away in quest of the sound – goat, satyr, and Ægypan, incubus, succubus and lemur, twisted toad and shapeless elemental, dog-faced howler and silent stutter in darkness – all led by the abominable naked phosphorescent thing that had squatted on the carved golden throne, and that now strode insolently bearing in its arms the glass-eyed corpse of the corpulent old man. The strange dark men danced in the rear, and the whole column skipped and leaped with Dionysiac fury. Malone staggered after them a few steps, delirious and hazy, and doubtful of his place in this or in any world. Then he turned, faltered, and sank down on the cold damp stone, gasping and shivering as the daemon organ croaked on, and the howling and drumming and tinkling of the mad procession grew fainter and fainter”.

It is the very nature of city life and modernity that Lovecraft seems to rail against while also rendered trembling by its hidden horrors, something every horror story seems to tell in allegory (as it is a distinctly modern genre); expressing the psychological struggles of our age, the rationalism of which refuses to comment on or even accept.

Something Lovecraft occasionally commented on in his stories, that struck me as being even more relevant today than a hundred years ago, was the creeping encroachment of the State on everyday community life. In a prescient passage at the beginning of The Shadow Over Innsmouth, intuiting the coming horrors of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (not to mention what Western governments would surreptitiously get away with), it starts: “ During the winter of 1927-28 officials of the Federal government made a strange and secret investigation of certain conditions in the ancient Massachusetts seaport of Innsmouth. The public first learned of it in February, when a vast series of raids and arrests occurred, followed by the deliberate burning and dynamiting – under suitable precautions – of an enormous number of crumbling, worm-eaten, and supposedly empty houses along the abandoned waterfront. Uninquiring souls let this occurrence pass as one of the major clashes in a spasmodic war on [prohibition] liquor.

Keener news-followers, however, wondered at the prodigious number of arrests, the abnormally large force of men used in making them, and the secrecy surrounding the disposal of the prisoners. No trials, or even definite charges, were reported; nor were any of the captives seen thereafter in the regular gaols of the nation. There were vague statements about disease and concentration camps, and later about dispersal in various naval and military prisons, but nothing positive ever developed. Innsmouth itself was left almost depopulated and it is even now only beginning to show signs of a sluggishly revived existence.

Complaints from many liberal organisations were met with long confidential discussions, and representatives were taken on trips to certain camps and prisons. As a result, these societies became surprisingly passive and reticent. Newspaper men were harder to manage, but seemed largely to cooperate with the government in the end… People around the country and in nearby towns muttered a great deal among themselves, but said very little to the outer world”.

The name Necronomicon, meaning Book of the Dead, was an invention of Lovecraft’s. In his stories the book and its fictional author, the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred, are often referenced as the source of, or at least having some malevolent influence on, the characters and events that unfold. Many such texts, some fictional and some not, occur throughout Lovecraft’s work.

Book of the Dead was inspirational to Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead2 franchise, and Lovecraft’s influence can be seen in other popular fiction of the late twentieth century. Most recently, The Colour Out of Space, a story that predicted science fiction like that of the X-Files decades beforehand, was adapted into a 2019 film starring Nicholas Cage. The writer also had a palpable influence on the filmmaker John Carpenter, The Thing (1982) starring Kurt Russell being similar in many ways to the story At the Mountains of Madness, and Carpenter referenced Lovecraft’s influence directly in his 1994 film In the Mouth of Madness, starring Sam Neil (for more about the film, see my article IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS – REVISITED3), Carpenter commenting: “I’ve always wanted to tackle H. P. Lovecraft. I’ve always wanted to do something with him. It’s very hard because he describes indescribable horror. What is it? What does it look like? It drives people mad when they [read] it.” The heavy metal band Metallica have even given a nod to Lovecraft in the instrumental track The Call Of Ktulu4 on the album Ride The Lightning.

Cthulhu (spelt in multiple variations) is the monster of Lovecraft’s creation most synonymous with the Lovecraftian; the bulbous, tentacled thing flapping its wings as it drifts implacably toward its next victim, taking up most of the space on the hard front cover of Necronomicon. Posthumously, this monster grabbed the collective imagination of Lovecraft fans so much that it became known as the Cthulhu Mythos, some, over the years, creating their own Cthulhu tales to add to Lovecraft’s already otherworldly creation.

One of Lovecraft’s major contributions to the horror genre was creating what have now become common horror movie tropes. In his short story The Hound, Lovecraft succinctly paints a scene that would later become a cliche to late twentieth century movie goers. “By what malign fatality were we lured to that terrible Holland churchyard? I think it was the dark rumour and legendry [sic], the tales of one buried for five centuries, who had himself been a ghoul in his time and had stolen a potent thing from a mighty sepulchre. I can recall the scene in these final moments – the pale autumnal moon over the graves, casting long horrible shadows; the grotesque trees, drooping sullenly to meet the neglected grass and the crumbling slabs; the vast legions of strangely colossal bats that flew against the moon; the antique ivied church pointing a huge spectral finger at the livid sky; the phosphorescent insects that danced like death-fire under the yews in a distant corner; the odours of mould, vegetation, and less explicable things that mingled feebly with the night-wind from over far swamps and seas; and, worst of all, the faint deep-toned baying of some gigantic hound which we could neither see nor definitely place. As we heard this suggestion of baying we shuddered, remembering the tales of the peasantry; for he whom we sought had centuries before been found in this selfsame spot, torn and mangled by the claws and teeth of some unspeakable beast”.

Howard Phillips Lovecraft died at the age of forty-six on the morning of March 15, 1937, at the Jane Brown Memorial Hospital. He had been suffering for some time from bowel cancer and kidney disease.

Even a century after H. P. Lovecraft published his first story, the genre of fiction he created is still not clearly defined. I have seen it described as speculative fiction, science fiction-horror, and fantasy-horror to mention just three, but it is a sure thing that he started something that pulled back the veil on the shadow side of the modern psyche; it’s daylight world filled with shiny technology and beliefs grounded in rational materialism, with all of human nature’s instincts, superstitions and a yearning for the phantasmagoric, lurking just below the surface with entropic intensity waiting to burst out, like the otherworldly power of a Lovecraftian demon-god like Cthulhu or Yog-Sothoth.

Lovecraft pioneered both sci-fi and modern horror fiction. Though his prose may seem almost atavistic to some, his astute mind was grapling with the technological breakthroughs of the twentieth century and, in allegorical form, I think warning us of the Faustian demonic powers that are being unleashed by humanity in its semi-ignorant desire to obtain knowledge and power of nature and three dimensional space, not reckoning with the psychic and metaphysical consequences such things have inflicted on man himself. Like Faust, most of Lovecraft’s characters are hungry for knowledge and discovery, and it is what they discover and unleash that is truly horrific; what better description of modern man than when one thinks of the atomic bomb, manufactured bio-weapons, social and genetic engineering, and the rapid disruptive approach of artificial intelligence.

The final word should be given to Lovecraft himself. When commenting on human nature, he once said: “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown”.

1

2

3

https://oliverp.substack.com/publish/posts/detail/47610496?referrer=%2Fpublish%2Fposts

4

IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS – REVISITED

The other day, during my usual YouTube rummagings, I came across a video by JoBlo Horror Originals, titled: IN THE MOUTH OF MADNESS (1994) Revisited - Horror Movie Review. The film is one of John Carpenter’s lesser known works, but definitely one of his most curious.