Before I start riffing about 28 Days Later, I have to be honest about my reasons for watching the film. Usually, I would stay well clear of zombie and vampire movies, as I feel the genre has been done to death by cynical producers, cashing in on the downward pull of trash culture that has such a large audience (give people McDonald’s and they’ll eat it, sort of thing). But after watching a documentary about how digital technology has influenced filmmaking, presented by Keanu Reeves, titled Side by Side1, my curiosity was peaked by an interview with Danny Boyle (the director of 28 Days Later). He talked about how he was influenced by a school of low budget filmmaking from Denmark called Dogma 95, which experimented with early video cameras. Though the picture quality was inferior to film, Boyle saw the potential. 28 Days Later was largely shot on the Canon XL1. Though only standard definition (less than half the resolution of full HD), the camera offered the ability to change lenses. This meant setting the camera up was made easier and quicker, as video cameras are lighter and more user friendly, giving the filmmakers the ability to film many more angles for editing options later in post. So as a cineaste, I couldn’t help but watch it again with that in mind.

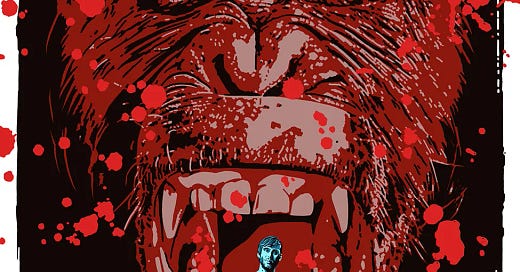

The film begins with multiple images of a society in crisis flashing before us. As the camera pulls out, we see a chimpanzee strapped to a chair, its head covered in electrodes. Moments later, a group of animal rights activists break in, to find other chimpanzees locked in perspex boxes. A scientist appears, to warn them against releasing the animals, as they are infected with a dangerous virus called ‘RAGE’. In their fanatical idealism, they ignore him, only for one of their party to be bitten and go on a rampage, infecting them all.

The chimpanzee living a tortured version of a modern life (through a screen) struck me as a kind of end-stage Darwinism. According to the now popular belief, we are descended from primates, along with the notion of survival of the fittest (something Darwin never originally said). The chimpanzee infecting the activist with ‘rage’ immediately made me think of the effect such a way of thinking can have on human behaviour. Random selection implies that our place here is not sacred or intended, it is simply good luck; and if we’re not careful, we can vanish just as easily. Anxiety inducing to say the least. The scientist represents an attempt at creating something to alleviate such a condition, but that just creates a somnambulism (sleep walking) in the masses; represented both by the chimpanzee mindlessly consuming the images on multiple televisions, and the unthinking gangs of roaming zombies.

Immediately after, we see Jim (Cillian Murphy) awaken naked on a hospital bed. He wanders around the empty corridors of the hospital, before searching the dead streets of London alone. One side of his head has been shaved and he has a surgical scar. Literally, something pathological has been removed from his head. Such a beginning for a protagonist has become a zombie movie trope, like Alice (Milla Jovovich) in Resident Evil and Rick (Andrew Lincoln) in The Walking Dead. They represent the few modern individuals who have ‘woken up’ to the reality of the world they live in. Unlike the mass of mindless zombies, they see the metaphorical emptiness of the environment, as Jim now can, after his life-changing medical procedure.

The first place Jim seeks refuge is a church, but no sooner has he entered, a high camera angle showing a wooden crucifix above him, is he met by ‘the end is extremely f*cking nigh’ scrawled on a wall and a pile of dead bodies before the altar. A zombie priest then attacks him. The metaphor here is that Christianity is well and truly dead. Its vestiges may remain, but it offers no sanctuary from the onslaught of the contemporary thinking hinted at the beginning of the film. Not only that, but the first zombie that attacks Jim is a priest; the Church isn’t just helpless anymore, but exacerbates his malaise.

Jim returns to his family home, to find his parents dead and a note that reads: “Jim – With endless love, we left you sleeping. Now we’re sleeping with you. Don’t wake up. X”. As already explained, this re-enforces the sense of mass somnambulism, to which Jim can now not go back.

By this time in the story, he has teamed up with Selena (Naomie Harris). After seeing flashing lights from a high-rise apartment building, they decide to investigate. Chased by zombies, they make it to the source of the lights, where they meet Frank (Brendan Gleeson) and his daughter, Hannah (Megan Burns). They hear a broadcast on a windup radio that there is a safe zone near Manchester, so they drive north in Frank’s black taxi cab; a wide shot of a flower field beautifully rendered as an impressionist painting.

Before they reach Manchester, they take refuge in the ruins of an old monastery. There, they see a family of horses gallop by, seemingly oblivious to the sufferings of mankind. As they run away, Frank blows them a kiss. Music swells up underneath, giving the animals an air of divinity and grace. This is reflected by the peace and uninterrupted rest they are allowed within the walls of the old monastery. For a brief time in the middle of the film, they have found an eternal space where nature and the human spirit can simply be, unmolested. But, the next morning they’re on the road again.

Soon after, Frank becomes infected and is killed. The others manage to make it to a mansion that a small band of British soldiers have turned into a makeshift fort. In the lobby, a replica statue of Laocoön stands above them; the mythical priest that warned the Trojans not to open the gates for the giant wooden horse. The gods punished him for going against their will and sent giant serpents to eat him and his sons.

From Jim’s first conversation with the commanding officer, Major Henry West (Christopher Eccleston), it’s clear something is not quite right about him and his men. West gives Jim a nasty surprise by introducing him to an infected soldier chained up in a courtyard, with the intent of studying his behaviour, in a crude version of the scientist at the beginning of the film. West says of him: “He’s telling me he’ll never bake bread, plant crops, raise livestock. He’s telling me he’s future-less.” Like the chimpanzee parody of modern man in the first scene, West articulates the philosophical vacuum of modern man. Without a sense of purpose, no one can imagine their future, just survive; exactly the situation Jim has found himself in since he woke up.

That evening in the middle of dinner, all hell breaks loose as a hoard of zombies attack the mansion. From hereon in, the statue of Laocoön is seen repeatedly; fleeting in close up or looming behind the characters. Like Cassandra, he was not heeded by the Trojans, just as the activists and West will not see sense and destroy the infected chimpanzees and soldier. The soldiers become increasingly sexually aggressive toward Selena and Hannah, and after a botched attempt to execute Jim, all discipline falls apart. Soon afterwards, Jim releases the infected soldier into the mansion, allowing him, Selena, and Hannah to escape.

The film ends with the three in a secluded cottage, a giant HELLO sign spread on the grass outside. A jet flies over and Selena asks: “Do you think he saw us this time?” They are happy and full of hope as they look up, looking skyward toward the heavens. Perhaps this represents them regaining their faith; the pilot and aircraft offering salvation like a beneficent god, for now they have survived, and can begin living for a future again.

Your newsletter story of 28 Days Later had a lot of good information and ‘peaked my interest. I’m going to give this one a re-watch as well.